By Paige S. Pandora

University of Southern Maine

Biddeford and Saco were up-and-coming areas when the Civil War struck.

Biddeford’s population grew significantly from 1830-1860. People were migrating to the area to work in the mills and the supporting businesses that supplied them. Biddeford and Saco were both already very successful in their agricultural endeavors, but industry was on a steady rise.

Business in Biddeford began to expand as entrepreneurs took advantage of the river and sea access in the area. Due to these financially advantageous factors, heavy Irish and Canadian immigration occurred. The 1830 and 1860 Biddeford census show a rise from 1,995 residents to 9,349 residents.

During the Civil War, Maine laborers worked in logging, milling, papermaking, built ships, fished, and processed fish; mined and cut granite and slate; cut and shipped ice, as well as farmed the state's rocky soils. Biddeford and Saco were well known for ice harvesting, granite cutting, and cotton textile manufacturing. Businesses that supported the war did well and were able to hire more employees. Biddeford and Saco were luckier than other towns and cities due to having access to raw materials.

The ice harvesting flourished during the 1870s and 1880s. Ice harvesting began to expand as the demand for chilled food and drinks grew. Ice was the primary way of preserving food until freon refrigeration was created in the early 1900s. Prior to the Civil War and Reconstruction Era, ice was a luxury. Once citizens financially recovered from the hardship of the war, perishable items such as dairy and produce became more popular, which in turn required more preservation. Ice harvesting was not only a local, state or national trade, ice was shipped all over the world as far as South America, India and China.

Granite quarries became more popular in Biddeford during the Civil War. Several quarries opened during this period to include, the Andrews Quarries, Ricker Quarry, and the Gowen Emmons Quarry. Biddeford’s granite and slate cutting was a crucial part of their economy and even helped support the build of the Western Railroad in 1872. Andrews Quarry saw great success in 1886 when James Andrews and Sons began a contract for the New York Harlem Bridge and a bridge in Philadelphia to provide 25,000 yards of stone to New York and 600 for Philadelphia.

The cotton textile manufacturing industry became very significant in Biddeford once the Laconia Mills and Pepperell Mill were established. Saco Water Power Company of York Manufacturing, built the Laconia Mills on the Biddeford side of the river in 1844, then started Pepperell Manufacturing Company in 1850. Once these two mills were established this mill district came to be one of the largest cotton milling facilities in the country. Even when cotton manufacturing became scarce, they worked on army tents, wagon covers, heavy drills, and jeans for military use.

Raw cotton was imported from the Southern States then manufactured in textile mills. During the years of the war, cotton manufacturing became extremely challenging. The Union blockades cut off the export of cotton which caused extreme rises in bids from English buyers. With everyone facing financial hardships during the war, manufactures shut down their mills and sold off their cotton. They saw the opportunity for making fast cash off the high bidders. This further drove the two towns into financial crisis.

The Providence Journal in August 1862 said, “The Production of cloth is now not one-quarter of the producing in common times, and every week it is growing smaller. Mills are stopping in every direction, and probably not one-half of those now running will be in operation the 15th of August.”

The Pepperell Mill in Biddeford was the life blood for the small city during the 1800’s and early 1900’s as the textile industry in Maine thrived. Like ice, this industry was international and products shipped all the way to India and Sri Lanka. The Laconia Mills were one of the earliest established textile mills on the Biddeford side of the Saco River. The Laconia Mills were a critical asset to the city during the war but were unable to recover from the economic hardships they faced during and after the Civil War. They were later bought by Pepperell Manufacturing Company by 1900 and became Laconia Division of the Pepperell Mills.

As more businesses and industries were using the local water ways advantageously, nearly 17 sawmills were erected in Saco by 1800. The Saco River’s waterpower aided in inflating the local lumber industry. J.G. Deering Lumber Company was a significant sawmill founded by Joseph G. Deering in 1866 on Spring Island in Biddeford near Bradbury Dam. J.G. Deering was eventually renamed J.G. Deering & Son Company once Joseph G. Deering’s son Frank Cutter Deering joined the business. The Saco River Driving Company served as the wood operation and river driving subsidiary of J. G. Deering & Son.

With the rise of industry in Biddeford during the 1860s, thousands of French Canadian, Irish, and some west European immigrants migrated to Biddeford and Saco to work in textile mills, ice harvesting manufactures, lumber mills, and granite quarries. Immigrants not only served to support the industries of Biddeford and Saco, but many also opened their own small businesses. The influx of immigration created cultural but more specifically, religious changes to the two towns.

Canadians made up for 25 percent of all immigration to Biddeford and Ireland made up an additional 12 percent, both were heavily Catholic demographics. Prior to the influx of immigrants, Biddeford only had one Catholic church; the Church of the Immaculate Conception. There only being one Catholic Church caused conflict between French Canadian Catholics and Irish Catholic. The animosity resulted in the founding of Saint Joseph’s Church in 1870 for French-Canadian Roman Catholics.

Prior to the attack on Fort Sumter, the Union and Journal, out of Biddeford, tracked the secession of Southern states. As portrayed in the Union and Journal, Northerners believed the attack on Fort Sumter was not likely, because Boston papers stated that Confederate President Jefferson Davis had telegraphed to Charleston not to prevent the landing of Union supplies.

On April 12th, 1861, Northerners, Mainers and citizens of Biddeford and Saco were angered by the surprise and the tragedy of the attack.

Soon after the surrender of Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln called nationally for volunteers, requiring Maine to raise one regiment of infantry for three months of Federal service. The first company of Biddeford volunteers left in May of 1861.

By October of 1862, more than half of all able-bodied men were in the armed services.

By the end of the war, 924 men had served the Union.

B Company, Fifth Maine Infantry Regiment, served as the most Biddeford dense Maine company during the Civil War. B Company served as Home Guards meaning they were called into service for the protection of public property within the State.

By the end of 1861, Biddeford and Saco citizens were a part of almost all Maine regiments participating in the Civil War.

These regiments included 1st Maine Infantry, 3rd Maine Infantry, 4th Maine Infantry, 5th Maine Infantry, 6th Maine Infantry, 7th Maine Infantry 8th Main Infantry, 9th Maine Infantry, 10th Maine Infantry, 12th Maine Infantry, 13th Maine Infantry, 1st Maine Calvary, 1st Battery of Mounted Artillery, and 5th Battery of Mounted Artillery.

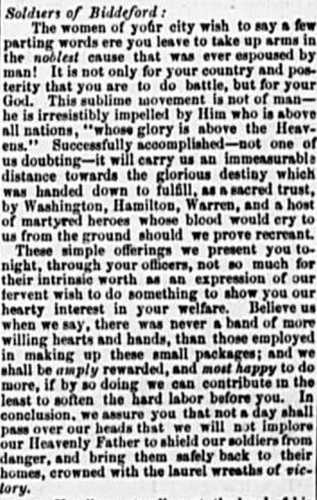

While there were no battles fought in Maine or the two cities, the citizens back home supported the war in their own way. In May of 1861, local fundraising began in order to support the families of those with enlisted Soldiers. Women and men who remained home started a Soldier Relief Society, and supplies were sent to sick and infirmed Soldiers on the frontlines. Local women teamed up to create care packages and letters to Biddeford and Saco Soldiers. On behalf of the women of Biddeford, the Union and Journal published the following message, “Believe us when we say, there was never a band of more willing hearts and hands, than those employed in making up these small packages; and we shall be amply rewarded, and most happy to do more, if by so doing we can contribute in the least to soften the hard labor before you.”

During the Civil War, the State of Maine provided aid to the families of soldiers. In 1862, 257 families were supported. In 1863, 269 families were supported. In 1864, 263 families were supported. Lastly, in 1865, 221 families were supported.

The amount of Maine State bounty paid to volunteers, drafted men, substitutes, and all other recruits for the army and navy, between April 12, 1861, and December 31, 1865, was $4,584,636. Biddeford paid servicemen $145,497 and Saco paid servicemen $105,749.

The high cost of soldier's bounties paid by the cities, had an overall negative economic impact upon Biddeford and Saco.

The war years in the city were difficult; high taxes, city debt, and layoffs. The ensuing joblessness and poverty took their toll. The cities faced a huge debt crisis and many citizens refused to pay the tax assessments imposed by the city government.

Layoffs were common for mill workers, many of which were forced to rely on the city's Poor Farm for Assistance program. In the 1861-62 Annual Report, the Overseer of the Poor stated that 873 people were assisted either on or off the farm, and a second house had to be procured to house all the destitute people in the city.

The month of April in 1865, Northerners, Mainers, and Biddeford and Saco residents faced a frenzy of emotions.

On April 3rd, the Union celebrated the capture of the Confederate capital, Richmond. The Union and Journal published the following message on April 7th, “The bells of Biddeford and Saco were running on Tuesday, and 100 guns were fired in honor of the fall of Richmond. In Saco in the evening the Town Hall was thrown open, which was packed by a joyful crowd. Speeches, singing and cheers were the order of the evening, and were appropriate and enthusiastic.”

April 9th marked Confederate Robert E. Lee’s surrender. Like, April 3rd, Biddeford and Saco rejoiced in the streets as the news of Lee’s surrender spread like wildfire. “All places of business were closed, and the mills shut down. Flags were to be seen everywhere, and the demand for red, white, and blue ribbons exhausted the millinery shops in short metre.”

The first two weeks of April 1865 represented a time of celebration that the Civil War was over. What was two weeks of celebrating abruptly turned into mourning; President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 15th.

Reality dawned on the citizens of Biddeford and Saco as soldiers returned home. But truth struck the family members and friends of those who would not return home.

By the year 1866, the majority of Biddeford were mourning loved ones who scarified their lives for the war. An article posted on January 6th, 1866 by the Union and Journal said, “It is true that there is a skeleton in every house, it may also be true that there is one in every heart; and God help and tenderly pity them who cannot lock the unwelcome visitor in some who cannot lock the unwelcome visitor in some remote recess, but at whose musings the sorrowing shadow will unbidden come.”

From the Union and Journal (Biddeford, Me.), May 10, 1861, p.2.

From the Union and Journal (Biddeford, Me.), May 10, 1861, p.2.